Description

Cat#:

Format: CD / ALBCD-025

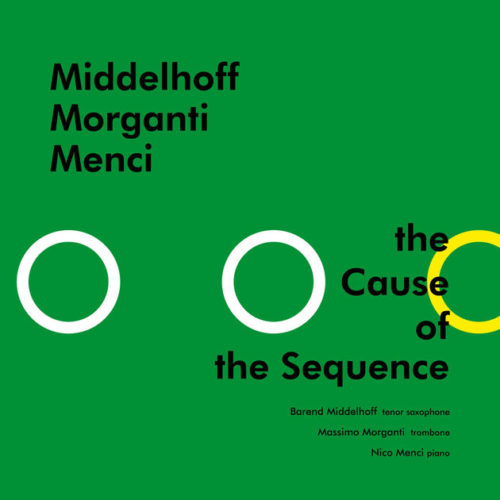

ARTIST: Middelhoff, Morganti, Menci

TITLE: The Cause Of The Sequence

JAN: 4560312310250

Lineup:

Barend Middelhoff (tenor sax)

Massimo Morganti (trombone)

Nico Menci (piano)

Rec data:

Recorded on May 30-31, 2014

Recording engineer: Marco Ferri at Ermes Studio, Vignola Italy

Mixing engineer: Chris Weeda, Amsterdam

Mastering engineer: Luca Bulgarelli

Photography: Andrea Frascari

Liner notes by Roberto Paviglianiti

Executive producer: Satoshi Toyoda – Albore Jazz

Liner notes

I first heard about Albóre Jazz from Roberto Gatto, in the summer of 2010, before a concert of his in Castel Gandolfo, near Rome. “It’s a serious label,” he said enthusiastically, “managed by the producer Satoshi Toyoda, who always thinks about the artist’s needs first.” The label continued to grow and became well-known in the international jazz scene thanks to the release of its many interesting albums. Its twenty-fifth CD is no exception: “The Cause Of The Sequence”, played by the trio Barend Middelhoff, Massimo Morganti and Nico Menci.

It’s an unusual combination: tenor sax and trombone, who are ready to play together or exchange roles as protagonist, and piano, skilled in building both a flexible rhythmic framework and adding to the overall expressiveness with well-measured movement. The three work towards precise positioning in terms of sound space and refer continuously to melodic phrases and linear, singable themes. Much importance is also given to the parts left blank in the score, which let the music breath and loosen the stitching in the musical fabric, allowing the tonal character of the instruments to stand out even more. All this develops over a medium-slow tempo, playing on ideas that hark back to the cool jazz scene and to chamber music situations, creating an elegant, open ensemble, with a subtle power of communication. The trio exudes clarity of expression in passages like Middelhoff’s Ballad For Anna, dedicated to his wife, who he met in France a few years ago, embracing a life full of unknown adventure together, to later settle down in Bologna where they now live. It is a ballad full of sweetness and poetry, in which the tenor sax with its puckered breathing, always plays in the foreground, as if to emphasize a lasting, deep and sincere love. At the end of the tracklist we find an equally expressive piece, Musiplano. The theme was recorded by Massimo Morganti in 2012 with a piano less quartet and is here presented in a more moderate version, where depth of style and embellished outlined to the piece can be found in Nico Menci’s piano itself. Morganti was also responsible for the arrangement of Angel Eyes by Matt Dennis, previously recorded by the trombonist with Marco Postacchini’s octet.

Through alternating solos, each player is drawn into this standard in the same way, and the resulting overall interpretation is rich in essentiality. The other remake on the album is Nothing To Lose by Henri Mancini, in which the trio proves it can venture into any repertoire without compromising its personal sound, which remains well-rooted and very recognizable throughout. Here the melody is played by the trombone and supported by saxophone. This creates a striking impact, a haunting feel and offers attractive shades of tone.Middelhoff said about this piece: “We went into the studio and we just played, in a natural way, without forcing anything and without complex arrangements.” The fluency of form and naturalness of both harmonic, rhythmic and melodic developments, clearly pervades the whole recording, as we can hear in Unison Party for example, where sax and trombone move hand in hand in a particularly strong fusion of tones. These features also emerge in the tracks Big Belly Blues and Slow White Blues, where Nico Menci shows how he can work without drums or double bass, thanks to his precise use of rhythm. The title track, meanwhile, is a symbol of spontaneity: it begins with written harmony and the thematic sequence then develops freehand, nourished by a steady stream of inspiration. As a whole, the trio shows a defined personality, thanks to the intelligence and dedication of the individual musicians. Their serious approach avoids any monotony which, for such a structured album, could have proved the biggest danger.

— Roberto Paviglianiti (English translation by Trevor Briscoe)

Voices

A very cool combo – one that features the trombone of Massimo Morganti, tenor of Barend Middelhoff, and piano of Nico Menci – all working together without any other instrumentation at all! The style means that the piano handles as much of the rhythm as it does the melody – making for these warm grooves that are really wonderful – as lyrical as they are soulful, and with a strength that really drives both of the horn players forward too – so much so you don’t miss the bass and drums at all! At most points, the style is very swinging – hardly the kind of airy experiment you might guess from the format – and both Middelhoff and Morganti win us over right away with the strength of their phrasing together, and the range of their solos when they break out. A wonderfully fresh record, and a delight all the way through – with titles that include “Unison Party”, “Big Belly Blues”, “Ballad For Anna”, “Musiplano”, “The Cause Of The Sequence”, and a nice cover of Henry Mancini’s “Nothing To Lose”. © 1996-2015, Dusty Groove, Inc.

A very cool combo – one that features the trombone of Massimo Morganti, tenor of Barend Middelhoff, and piano of Nico Menci – all working together without any other instrumentation at all! The style means that the piano handles as much of the rhythm as it does the melody – making for these warm grooves that are really wonderful – as lyrical as they are soulful, and with a strength that really drives both of the horn players forward too – so much so you don’t miss the bass and drums at all! At most points, the style is very swinging – hardly the kind of airy experiment you might guess from the format – and both Middelhoff and Morganti win us over right away with the strength of their phrasing together, and the range of their solos when they break out. A wonderfully fresh record, and a delight all the way through – with titles that include “Unison Party”, “Big Belly Blues”, “Ballad For Anna”, “Musiplano”, “The Cause Of The Sequence”, and a nice cover of Henry Mancini’s “Nothing To Lose”. © 1996-2015, Dusty Groove, Inc.

テナー、トロンボーン、ピアノという組み合わせは珍しいが、聴いてみると意外なほどしっくり響いて来る。フリー系の即興ではなくて、むしろウェストコースト系といってもいい、大人の対話が聴ける演奏だ。欧州のミュージシャンらしく楽器コントロールは完璧だし、ソロの構成もアンサンブル部分とのバランスも見事にコントロールされている。通好みのハイレベルな演奏といってもいい。特に、楽器の演奏に興味のある方にはぴったりの一枚。フロント二本が時にユニゾン、時にアンサンブルを奏で、ピアノがバッキングするというパターンで即興部分へ突入する。テナーの音色は明らかに後期スタン・ゲッツの影響が大きい。(渋谷店 瀧口秀之)

テナー、トロンボーン、ピアノという組み合わせは珍しいが、聴いてみると意外なほどしっくり響いて来る。フリー系の即興ではなくて、むしろウェストコースト系といってもいい、大人の対話が聴ける演奏だ。欧州のミュージシャンらしく楽器コントロールは完璧だし、ソロの構成もアンサンブル部分とのバランスも見事にコントロールされている。通好みのハイレベルな演奏といってもいい。特に、楽器の演奏に興味のある方にはぴったりの一枚。フロント二本が時にユニゾン、時にアンサンブルを奏で、ピアノがバッキングするというパターンで即興部分へ突入する。テナーの音色は明らかに後期スタン・ゲッツの影響が大きい。(渋谷店 瀧口秀之)

蘭国出身、伊ボローニャ在住のゲッツ直系テナー奏者ミッデルホフの陽光あふれるアルバム。優秀なアレンジャーでもあるハートウォーマーなトロンボーン奏者モルガンティ、硬派でリリカルに躍動感をつけるピアノ奏者メンチとの変則トリオ。柔らかな色彩を放つ2管ハーモニー、洒脱なやりとり、歌心ある双方のアドリブ対比も愉しく、ピアノがリズム陣でもある溌剌・爽快な寛ぎ空間。爽やかな甘さ微かな哀愁も薫るおおらかな演奏をコンサートホールど真ん中の臨場感ある録音で。新鮮な朝の空気のように心の中のリフレッシュ間違いなし!(Suzuck)

蘭国出身、伊ボローニャ在住のゲッツ直系テナー奏者ミッデルホフの陽光あふれるアルバム。優秀なアレンジャーでもあるハートウォーマーなトロンボーン奏者モルガンティ、硬派でリリカルに躍動感をつけるピアノ奏者メンチとの変則トリオ。柔らかな色彩を放つ2管ハーモニー、洒脱なやりとり、歌心ある双方のアドリブ対比も愉しく、ピアノがリズム陣でもある溌剌・爽快な寛ぎ空間。爽やかな甘さ微かな哀愁も薫るおおらかな演奏をコンサートホールど真ん中の臨場感ある録音で。新鮮な朝の空気のように心の中のリフレッシュ間違いなし!(Suzuck)

有楽町マルイ – MUSIC JOURNEY – Spring Selection / March-June 2015

有楽町マルイ – MUSIC JOURNEY – Spring Selection / March-June 2015

現代イタリアの上質なジャズをリリースするレーベル、アルボーレ・ジャズより素晴らしい1枚が届きました。オランダ出身で伊ボローニャに在住の、テナー奏者=バーレント・ミッデルホフによる、テナー〜トロンボーン〜ピアノという編成の”新クール・チェンバー・ジャズ”。軽やかでやさしい2管と、スウィンギンなピアノとのやり取りが実に面白い内容となっています。淹れたてのコーヒーのような、なんとも香りの良いアルバムです。(kozy)

オランダ出身のバーレント・ミッデルホフほか、マッシモ・モルガンディ、ニコ・メンチによる、2管+ピアノのトリオ。ミッデルホフとモルガンティによる温かくも説得力にあふれたホーンに、シンプルでありながらも洗練されたヴォイシングのピアノによるアンサンブル。ヨーロッパらしいクールなトーンも感じられる。

オランダ出身のバーレント・ミッデルホフほか、マッシモ・モルガンディ、ニコ・メンチによる、2管+ピアノのトリオ。ミッデルホフとモルガンティによる温かくも説得力にあふれたホーンに、シンプルでありながらも洗練されたヴォイシングのピアノによるアンサンブル。ヨーロッパらしいクールなトーンも感じられる。

Un repertorio costruito nel rispetto della tradizione. Una formazione molto meno consueta e, soprattutto, molto esigente. Una dedizione continua e appassionata alla melodia, alla linearità dell’esposizione.

Un repertorio costruito nel rispetto della tradizione. Una formazione molto meno consueta e, soprattutto, molto esigente. Una dedizione continua e appassionata alla melodia, alla linearità dell’esposizione.

Pianoforte, trombone e sax tenore – senza ritmica – costituiscono un ensemble con ampi margini di libertà, ma costringono allo stesso tempo i tre ad un costante supporto reciproco e ad un ascolto attento. È la chiave scelta da Barend Middelhoff, Massimo Morganti e Niccolò Menci per garantire l’equilibrio della musica: una libertà utilizzata per ampliare le possibilità degli interpreti, “costretti” ad articolare le frasi per garantire sempre comunque la gestione ritmica e armonica del discorso.

Barend Middelhoff, autore dei cinque brani centrali del lavoro, sembra voler giocare sul filo della difficoltà creata dal rispetto dei canoni espressivi del jazz con un combo simile. Sono brani che proseguono il discorso avviato dalle canzoni scelte per l’apertura, vale a dire due standard come Nothing to lose di Henry Mancini e Angel Eyes di Matt Dennis: composizioni concepite nell’alveo del mainstream, tenendone presenti le dinamiche e le motivazioni e cercando i riferimenti nel blues e nello swing. Il punto è ricreare, suggerire, sfruttare gli spunti dei brani con la “trazione anteriore” del combo, privo del sostegno della ritmica. I temi diventano così utili punti di partenza per le improvvisazioni dei tre, ma anche per contrappunti e risposte, gestite in maniera fluida e filante.

La conclusiva Musiplano – firmata da Morganti e già presente nell’omonimo disco del trombonista – affronta invece le attitudini più corali del trio: più eccentrica rispetto al resto del disco, disegna atmosfere più aperte, dove i tre possono intervenire maggiormente sulle sospensioni e sugli echi innescati dalle frasi. Senza il bisogno di dover evocare la ritmica, anzi utilizzando un passo differente rispetto agli altri brani, la composizione di Morganti mette in luce una ulteriore sfaccettatura del combo.

The Cause of the Sequence mette in luce perciò una soluzione praticabile al rapporto del musicista odierno con le tradizioni del jazz. Se la composizione e l’approccio generale proseguono il percorso dei grandi maestri del passato, la formula particolare scelta per dare corpo alla formazione sposta accenti e coinvolge nuove possibilità. A tutto questo va poi affiancato il valore portato dalle personalità dei singoli interpreti, la dialettica dei rispettivi rapporti con la tradizione, già mostrato nelle precedenti prove discografiche e nei concerti. Se appare abbastanza improbabile che una composizione dei nostri giorni diventi uno standard, è senz’altro plausibile scrivere musica che tenga presente le matrici che hanno caratterizzato i brani più celebrati ed eseguiti della storia del jazz, le qualità che li hanno fatti scegliere all’interno del songbook dei musical e risaltare come veicolo per le improvvisazioni di generazioni di solisti. Middelhoff, Morganti e Menci procedono così secondo il passo disegnato dalle orme dei giganti in una riflessione musicale sulle strade ancora disponibili all’interno del linguaggio, senza bisogno di dimostrare alcunché, ma senza, allo stesso tempo, costringersi in un ruolo subalterno o imitativo. – 24 Giugno 2015, Fabio Ciminiera Twitter: @fabiociminiera